With experts predicting that average temperatures will continue to climb across Nebraska over future decades, the state's corn crop could be at risk. Temperatures above 90 degrees can make pollen sterile, resulting in corn cobs that look like they badly lost a fight, only with missing kernels instead of missing teeth.

On late-summer mornings for about two weeks every year — after sunrise but before it gets too hot to do much of anything — corn stalks all over Nebraska mate with themselves.

The tassels sprout anthers, which release pollen, which fall onto the sticky silks below, sometimes on the same plant. Two months later, give or take, and, voilà, a fully-grown corn cob is ready for harvest.

The process supports some 23,000 Nebraska farmers and provides about $7 billion annually to the state.

But, scientists say, climate change could take a big bite out of Nebraska’s corn business, threatening an economic engine for the state and an important food source for an ever-hungrier world.

“Corn pollination almost all takes place between 8 o’clock and 10 o’clock in the morning,” said Tom Hoegemeyer, a former University of Nebraska-Lincoln agronomy professor who has studied climate change’s effects on corn. “If it’s hot early in the day, that’s really negative.”

For Hoegemeyer, who is also a member of the Elders Climate Action group of former UNL scientists, “negative” means a drop-off in corn production of at least 20% when climate change really starts to pinch around mid-century.

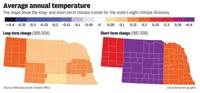

Nebraska’s temperature rose by about 1 degree over the past century. Climate models predict a temperature increase of 4 to 9 degrees by 2100, depending on how well the world can control greenhouse gases.

According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, a collaboration of 13 federal agencies, agricultural productivity in central and eastern Nebraska may fall by 50% toward the end of the century, although it would increase in the higher and cooler western half of the state.

Upsetting the pollination sequence is just one potential threat to Nebraska’s Cornhusker moniker.

Higher overnight lows in July’s critical growth weeks may also mean a less-robust crop. Longer and more frequent droughts would deplete moisture levels in the soil. Irrigation can help mitigate the damage, but surface and groundwater sources may not be quite so plentiful in a hotter, drier climate.

Heavier spring rainfall in the Midwest could lead to more soil erosion, another threat to yields. For example, in 2019, flooding took 421,958 acres out of production. By contrast, in 2018, only 25,048 acres were lost during a normal rainfall, according to a 2020 UNL agriculture report.

Corn was particularly hard-hit. The 2019 spring floods prevented 344,407 acres of cropland from being planted compared with a loss of only 18,956 acres in 2018.

If there is one group that can adapt to change, it’s farmers, who have a long history of managing all manner of threats: weather, pests, market shifts brought on by trade wars.

Billions of research dollars have led to insect-resistant plants, techniques for healthier soils and new crop rotation practices. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, farmers in the U.S. cultivated 330 million acres in 1910, supplying food and fiber for a population of slightly more than 92 million people.

By 2006, farmers plowed the same number of acres but produced enough crops for nearly 300 million. Nebraska farmers produced 26 bushels per acre in 1900. Today, they produce more than 180 bushels per acre.

Suat Irmak, a UNL engineering professor who has studied how climate changes affect agricultural productivity, said heat can have a “huge impact on crop growth and development.” For the last decade and a half, he said Nebraska has seen more extreme temperatures and precipitation events.

But he sees ways to mitigate the worst effects. A small amount of irrigation — an extra ¼ inch — can lower field temperatures by 7 to 10 degrees. No-till farming can also help keep soil cool. And genetics can create corn varieties that better withstand drought and high heat, Irmak said.

Corn itself is already remarkably adaptable. Hoegemeyer said there are tens of thousands of varieties. Corn has been grown on the outskirts of the Arctic Circle, from sea level to mountainous regions.

But a warming planet may bring tests of a different order.

“Climate change presents an unprecedented challenge to the adaptive capacity of U.S. agriculture,” a 2013 USDA report said.

Before he retired as head of the USDA’s National Laboratory for Agriculture and the Environment, Jerry Hatfield studied just what the effects could be.

Temperatures above 90 degrees can make pollen sterile, resulting in corn cobs that look like they badly lost a fight, only with missing kernels instead of missing teeth.

Hot, dry winds carry the same risk.

But it’s higher overnight lows that worry Hatfield the most. During the day, corn uses photosynthesis to create sugars. At night, the sugars spur cell growth. When nighttime temperatures are too high — above 50 degrees — the process is much less efficient. The stored energy gets wasted, and the plants don’t grow as well.

The UNL climate study reported that the number of high-degree temperature stress days — days over 90 degrees — will increase substantially by 2041-70.

“We think we have the capacity within adaptation to basically handle climate change scenarios until about 2050,” Hatfield said. “But then, as you look at the projections going forward, we may have to have some really innovative adaptation strategies to be able to cope without tremendous impacts on productivity.”

Tyler Williams, a UNL extension educator who focuses on climate issues, worries about how climate change will affect precipitation.

“In the No. 1 irrigated state for acres, we’re heavily dependent on groundwater and it’s not an infinite resource,” he said. “If we see a decrease in summer precipitation, or even the same precipitation with increased temperatures, we will put a strain on our groundwater and surface water resources.”

As snowpack levels decrease in the Rockies, another consequence of climate change, Nebraska rivers and streams that farmers also draw water from will drop as well.

For Andrea Basche, a UNL agronomy professor who specializes in climate adaptation, the concern is the variability of the rainfall. Heavier spring rains could keep farmers from getting in their fields. Because there aren’t crops to help hold the soil in place, spring rains lead to more erosion, stripping away the earth’s productive capacity.

Climate models and recent history both “point to more water in the winter, spring and fall and less in the summer, which is very bad for the crops we grow,” Basche said.

Another concern is an increase in the number of crop-destroying bugs. Climate change impacts the survival rate, geographical distribution, population size and other factors related to pests and diseases.

“If our winters get warmer, some pests who typically die in our cold winter may be able to survive,” Williams said.

They may also be hungrier. As temperatures warm, the metabolism of pests such as aphids and corn borers speeds up.

For Nebraska, an inability to adapt will lead to a severe economic hit. Nearly 46,000 farms and ranches contributed more than $21 billion to Nebraska’s economy in 2018. According to the Nebraska Department of Agriculture, 1 in 4 jobs in the state is related to agriculture.

The effects of bad crop years in the Midwest will likely ripple across the globe. The world’s population is expected to grow from 7 billion people in 2010 to nearly 9.8 billion in 2050.

According to a World Resources Institute report, food demand will increase 50% by mid-century. To meet demand, farmers will have to increase yields at a greater rate than historic trends, the report found. A disruption in any part of the world may be enough to raise prices, adding new stress for the food insecure.

Hoegemeyer retired from the university four years ago. But he often thinks of a student from Egypt who was studying at UNL in 2011.

The student said his father back home was constantly struggling to balance the family’s little money for fuel to get to work, to feed his family and for books so his children could attend school.

“When you increase food prices in lots of the vulnerable societies across the world, it’s going to force some really ugly decisions,” Hoegemeyer said. “We have a real responsibility to deal with climate change.”

One year ago: Photos, videos from catastrophic flooding in Nebraska

Flooding in Nickerson, 3.13

Floodwaters from Maple Creek spilled over Nebraska 91, blocking vehicle and train traffic in March near Nickerson.

Flooding in Wahoo, 3.13

Floodwaters from Cottonwood Creek spill over Nebraska 92 on Wednesday near the intersection with U.S. 77 west of Wahoo.

Flooding in Nickerson, 3.13

Rising water spills over the banks of Maple Creek as seen from a bridge near Nickerson on Wednesday.

Northeast Nebraska flooding

Flood images from northeast Nebraska this morning.

Aerial - Norfolk levee

— NEStatePatrol (@NEStatePatrol) March 14, 2019

Stop sign - St. Edward

SUVs under water - near Columbus

Trees - near Genoa pic.twitter.com/hQZAbLRb4I

I am gone

Over the dam at Chalco Hills

Arlington semi swept into floodwaters

St. Edward flooding

Gering roads

Ashland rescue

Creighton snow

Rock County north of Bassett

Just one of many roads out. These will not show up on the 511 map as they are country roads. Damage to roads and bridges plus blizzard conditions can have a deadly consequence. Please stay home (road is in Rock County N of Bassett, Carnes bridge) pic.twitter.com/2r03FymKJh

— NSP_TrooperGena (@NSP_TrooperGena) March 14, 2019

Spencer Dam collapse

U.S. 34 closed west of Seward

U.S. 81 north of Norfolk

O'Neill rescue

Rescuing calf

Big Blue in Crete

Ice chunks thrown onto road

Received these images from a Brig Gen with the @NENationalGuard taken on a county road near Elba.

Those are ice blocks on the road, brought there by flood waters.

Almost looks otherworldly. Now imagine these flowing in water. Don't drive through flood waters. pic.twitter.com/NwcIrTVIb5

— NEStatePatrol (@NEStatePatrol) March 14, 2019

Flooding in Ashland Area, 3.14

Floodwaters swarm over city of Lincoln wellfields northeast of Ashland on Thursday.

Flooding in Ashland Area, 3.14

Floodwaters move toward the edge of U.S. 6 northeast of Ashland on Thursday. The Platte is not expected to crest at Louisville until late Saturday night, and it is forecast to stay above flood level until late Monday or early Tuesday.

Flooding, Ashland

Mary Roncka and her husband Gene Roncka, accompanied by neighbor Kevin Mandina, are evacuated as floodwaters rise Thursday near Ashland.

Flooding, Hooper

Water floods a street Wednesday in Hooper.

Flooding, 3.14

Water covers the road Thursday northeast of Wahoo.

Flooding, 3.14

After the water receded at Emerson Estates Thursday afternoon, it revealed a home moved from its foundation.

Flooding, 3.14

Floodwaters at Emerson Estates near Inglewood swallowed a pickup and RV.

Flooding, 3.14

A truck is partially submerged in water at Emerson Estates near Inglewood on Thursday.

Fremont flooding

Floodwater and ice chunks cover Ridgeland Avenue east of Hormel Park in Fremont at around noon on Thursday. The water receded Thursday from the area of Emerson Estates, which was evacuated on Wednesday night.

Creighton bridge damage

Highway 91 at Lindsay

NDOT yard and buildings swept away on Highway 12

Rescued in boat

Craig Sorensen holds onto his dog, Ollie, as they are evacuated from their home near Bellwood on Thursday.

Spencer Dam

Milford flooding

Knox County Highway 14

Historic bridge over Loup destroyed

One tragedy among many: The bridge listed on the National Register of Historic Places near Sargent has been destroyed in the flooding on the Middle Loup River.

It was one of the few remaining steel truss bridges built in Nebraska in the early 1900s. 📸 April Kitt and Josey Wales pic.twitter.com/L65pbdljNw

— History Nebraska (@HistoryNebraska) March 15, 2019

Stranded cattle near Fremont

From the Fremont area this morning on the Platte. Each of those little islands has dozens of cattle on it, stranded with no place to go.

Our thoughts are with our agriculture industry as they will certainly feel the effects of this flooding. pic.twitter.com/PK8gpu2NMb

— NEStatePatrol (@NEStatePatrol) March 15, 2019

Highway 14 and 12 junction at Niobrara

Highway flooding

Floodwaters converge on U.S. 81 near Norfolk.

Genoa bridge

Floodwaters pass through a collapsed bridge on Nebraska 22 south of Genoa last week.

Stranded cattle

Cattle stand on dry land near patches of water near Fremont.

Flooding, 3.15

A worker sets out signs to block off Campanile Road on March 15 near Venice.

Flooding, 3.15

A truck towing an airboat drives through standing water Friday, March 15, 2019, to launch the boat and look for people who might need to be evacuated near Valley.

Wahoo to Omaha through Lincoln

Missouri River from Omaha

Highway 79 and North Bend evacuation

Tuxedo Park in Crete

A drone photo of Tuxedo Park in Crete taken Friday morning, showing flooding caused by the Big Blue River.

Platte River flooding at I-80

Platte River I-80 bridge (top) and Route 6 bridge near Ashland.

Oakland football field flooded

This is where I played football in high school.

Hoping for a speedy recovery for the people of Oakland, and other underwater rural communities. I have never seen so many NE communities flooded at once in my entire life. pic.twitter.com/QYCUo03i5o

— Graham Christensen (@grahamchristen) March 16, 2019

Flyover of Spencer Dam

Flooding near Plattsmouth, 3.16

BNSF locomotives sit submerged in Platte River floodwaters near Plattsmouth on Saturday.

Trying to keep floods from reaching Alda

Alda video

Bridge over Niobrara

What remains of Spencer Dam

Flyover of Highway 12 west of Niobrara

More video from @GovRicketts' flight today in northern Nebraska.

This is Highway 12 west of Niobrara. You can see where the bridge was and where it is now (a few hundred yards downstream).

Incredible damage to this area. Keep this area in your prayers. pic.twitter.com/hfBDOVQPjz

— NEStatePatrol (@NEStatePatrol) March 16, 2019

Wood River photos

Water surrounds Weather Service office

You may encounter some broken links on our webpage, but our forecasters remain hard at work forecasting and issuing warnings and products. We've moved operations to Hastings, NE.

Thanks, @NWSHastings! pic.twitter.com/duFbVpbGq5

— NWS Omaha (@NWSOmaha) March 17, 2019

Peru flooding, 3.17

Assistant fire chief Luke Winkelman stacks water bladders Sunday in Peru. Peru's water supply is limited since the water treatment facility was shut off when flood waters overtook the plant. Residents have been asked to conserve water usage.

Peru flooding, 3.17

Peru State College students and community members look out at the floodwaters March 17 in Peru.

Peru flooding, 3.17

Kody Smith helps moves clothes out of a flooded home Sunday in Peru.

Peru flooding, 3.17

Kyle Smith moves furniture out of a flooded home Sunday in Peru.

Peru flooding, 3.17

The top of a fire hydrant peeks out of the water Sunday, March 17, in Peru.

Peru flooding, 3.17

Floodwaters creep into the town of Peru in March, approaching a sign that is typically 1.75 miles from the water.

Peru flooding, 3.17

Kody Smith (left) and Kyle Smith move furniture out of a flooded house Sunday in Peru.

Peru flooding, 3.17

A family gets ready to haul a trailer full of furniture away from a flooded house in Peru on March 17.

Sarpy County flyover

West side of Columbus

Dog rescues

We understand how important your pets are.

So when troopers come to the rescue, the pets gets rescued too.

(Not pictured: a massive dog who got to ride in the NSP helicopter!)

Great work, troops! pic.twitter.com/ZOJwxV3o3X

— NEStatePatrol (@NEStatePatrol) March 17, 2019

Roads in northeast Nebraska

Save water Ride dirty in Lincoln

Bellevue flooding update

Task Force One

5 days and counting as NE-TF1 continues to assist not only the Nebraska National Guard but local first responders as well from this deadly flood. pic.twitter.com/Wfc0p70ivA

— NE-TF1 (@NE_TF1) March 18, 2019

Unloading in Peru

People in Peru, Nebraska unload water from One Way Church in nearby Plattsmouth. Peru’s water treatment plant was knocked out by flooding on the Missouri River pic.twitter.com/0HQoqLvSwF

— Fred Knapp (@fredmknapp) March 18, 2019

U.S. 77 south from Fremont

Rescuing calf in Fullerton

Nebraska City flooding

Nebraska City flooding.

Cooper plant

Cooper Nuclear Plant workers were being boated to and from the plant as both roads leading to the plant are covered by water.

Water flowing over levee L575 across the river from Nebraska City in Percival, Iowa

Water flowing over levee L575 across the river from Nebraska City in Percival, Iowa, in March.

NASA before and after images

Check out these images from @NASA.

Left is from March 2018.

Right is from Saturday.Troopers have shared images from ground and from the air, but to see if from space is even more eye opening. pic.twitter.com/2pg2zNS6fl

— NEStatePatrol (@NEStatePatrol) March 18, 2019

Steinhart Grain Terminal at Nebraska City

Steinhart Grain Terminal at Nebraska City.

Patrol flight of flooding

Among the many valuable things our NSP pilots do: stream real-time video to @NEMAtweets and the State EOC.

Here's what it looks like from the flight yesterday in southeast Nebraska up to the Omaha area. The video comes with a road overlay.

More Video: https://t.co/4zQscPl8NG pic.twitter.com/YQd5deV2nU

— NEStatePatrol (@NEStatePatrol) March 18, 2019

Valley roads

Offutt flooding

Like large portions of Nebraska, Offutt personnel are battling flood waters which started to creep onto the installation March 15. Get the full story here - https://t.co/o90sNK9o8i pic.twitter.com/9px7LetGJR

— OffuttAFB (@Offutt_AFB) March 17, 2019

Fixing the road

By the numbers

With a weekly newsletter looking back at local history.

September 27, 2020 at 08:30PM

https://ift.tt/2S2Ojdp

Rising temperatures put heat on Nebraska's $7 billion corn industry - Lincoln Journal Star

https://ift.tt/3gguREe

Corn

No comments:

Post a Comment