Kyle Henninger got an unwelcome surprise last fall when he sent three loads of corn to the mill.

His go-to buyer rejected the grain because it tested too high for aflatoxin — a fungal byproduct that the Lehigh Valley farmer had never faced before.

“The corn looked as good as the other corn looked,” he said.

Henninger was far from the only Pennsylvania corn grower to deal with aflatoxin in the 2020 crop.

The aspergillus fungus that produces the toxin prefers hot, dry conditions, which prevailed last summer, especially in the central and western parts of the state.

“We really often just hear of one grower here, another grower here who thinks they might have aflatoxin in any given year,” said Alyssa Collins, a Penn State field crop pathologist. “I think it was kind of unusual that we had a good deal of it this year, and that is almost certainly related to the fact that we had droughty conditions.”

Aflatoxin is an annual problem in the South, where fields are often parched during grain development, according to the University of Georgia.

Most years Pennsylvania has milder, more humid conditions that favor not aspergillus but a different fungus that produces vomitoxin.

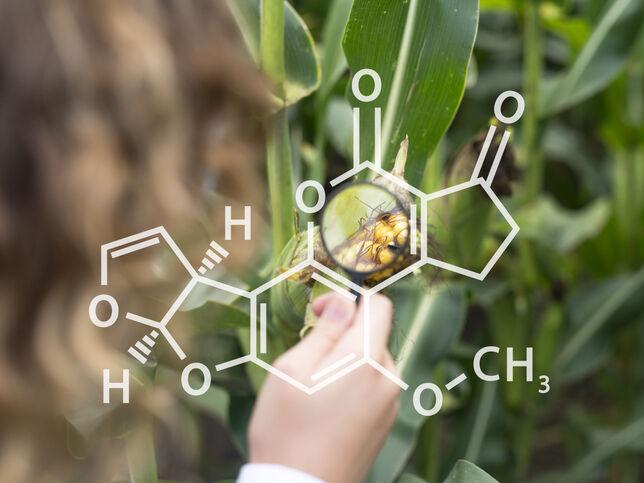

Aspergillus can be told from that fungus, and other ear molds, by its powdery texture and olive green color. It looks a bit like the relatively common penicillium and trichoderma molds, which are also green but have a bluish cast, Collins said.

Aspergillus gets into the ear through the silks and through bird and insect feeding or other damage to the husks.

Farmers can gauge their aflatoxin risk by considering how hot and dry the weather has been, and by scouting their fields.

In the week before harvesting for grain or silage, Collins recommends shucking a couple of ears to see how intact and clean they are. If there’s any type of ear mold, the farmer has a little time to get it identified and develop a plan.

“Maybe it’s not in all of your fields. Maybe it’s only in one or two depending on the hybrid or depending on when it got planted,” Collins said.

Grain with a toxin-producing mold should be harvested last, or at least separately from the other loads, and should remain segregated from the clean grain if possible.

It’s hard to assess the overall toxin level before harvest, but it’s good to think about it beforehand because the crop insurance company may want to send an adjuster or request samples for a claim, Collins said.

Growers don’t need to wait till they get to the mill to see how much toxin they have. Forage labs offer aflatoxin testing. It’s not cheap, but it could inform a farm’s marketing decisions, Collins said.

Adapting to the presence of aspergillus is more advisable than trying to control it with fungicides.

The pest rarely makes trouble in Pennsylvania, and farmers would have to spray well before they could tell if the treatment was warranted.

“It’s mostly knowing what you have when you have the problem that you can identify,” Collins said.

In the South, some farmers employ a non-toxin-producing aspergillus. Applied at silking, the fungus takes the space that would have been available to its dangerous kin.

But this treatment isn’t cheap, and because the fungus is a living organism, it can’t sit on the shelf indefinitely. This strategy would not often be cost-effective in Pennsylvania, Collins said.

The Food and Drug Administration and USDA place strict limits on aflatoxin levels in grains and feed, and for good reason, said Raj Kasula, vice president and chief nutrition officer at The Wenger Group, an agribusiness based in Rheems, Pennsylvania.

In livestock, aflatoxin can cause digestive system problems, weaken resistance to disease, cut feed intake and performance, and in some cases prove fatal. The toxin is carcinogenic and can be harmful to humans.

As a result, Wenger Feeds — the Wenger Group subsidiary that rejected Henninger’s loads — has a longstanding policy to test susceptible feed ingredients for mycotoxins, or toxins created by fungi, Kasula said.

It’s particularly important to keep aflatoxin out of swine feed, pet food, eggs and milk.

And while vomitoxin has the more gruesome name, it’s dangerous at concentrations of parts per million. Aflatoxin causes harm in just parts per billion.

“A smaller amount of it will cause a bigger problem,” Collins said.

When ear rots and ear molds are in play, farmers need to dry their grain below 14% moisture as quickly as possible after harvest. At that point, the fungus won’t be able to spread in storage, and that’s about the best a farmer can hope for.

“Mycotoxins are really notoriously stable, so roasting or adding stuff doesn’t really change the amount of toxin or the impact of the toxin that’s in there,” Collins said.

Henninger finally sold his three corn loads last fall to a small mill that wasn’t testing for aflatoxin, but by that point he had incurred extra expense for fuel and the driver’s time.

Northeastern grain buyers don’t routinely test for aflatoxin, but after his experience, Henninger said he wouldn’t be surprised if that soon becomes standard.

Collins doubts mills will go to that extent.

“It is expensive to do these tests,” she said, “so in a year where we’re not expecting, environmental conditions-wise, to get some of these issues, they don’t want to waste the money testing everyone.”

Still, she said, mills may test for aflatoxin in years when the weather has been conducive and word gets around about a problem.

The Link LonkFebruary 19, 2021 at 08:52PM

https://ift.tt/3bjMPVu

Corn Toxin Makes Rare Uptick in Pennsylvania | Main Edition | lancasterfarming.com - Lancaster Farming

https://ift.tt/3gguREe

Corn

No comments:

Post a Comment