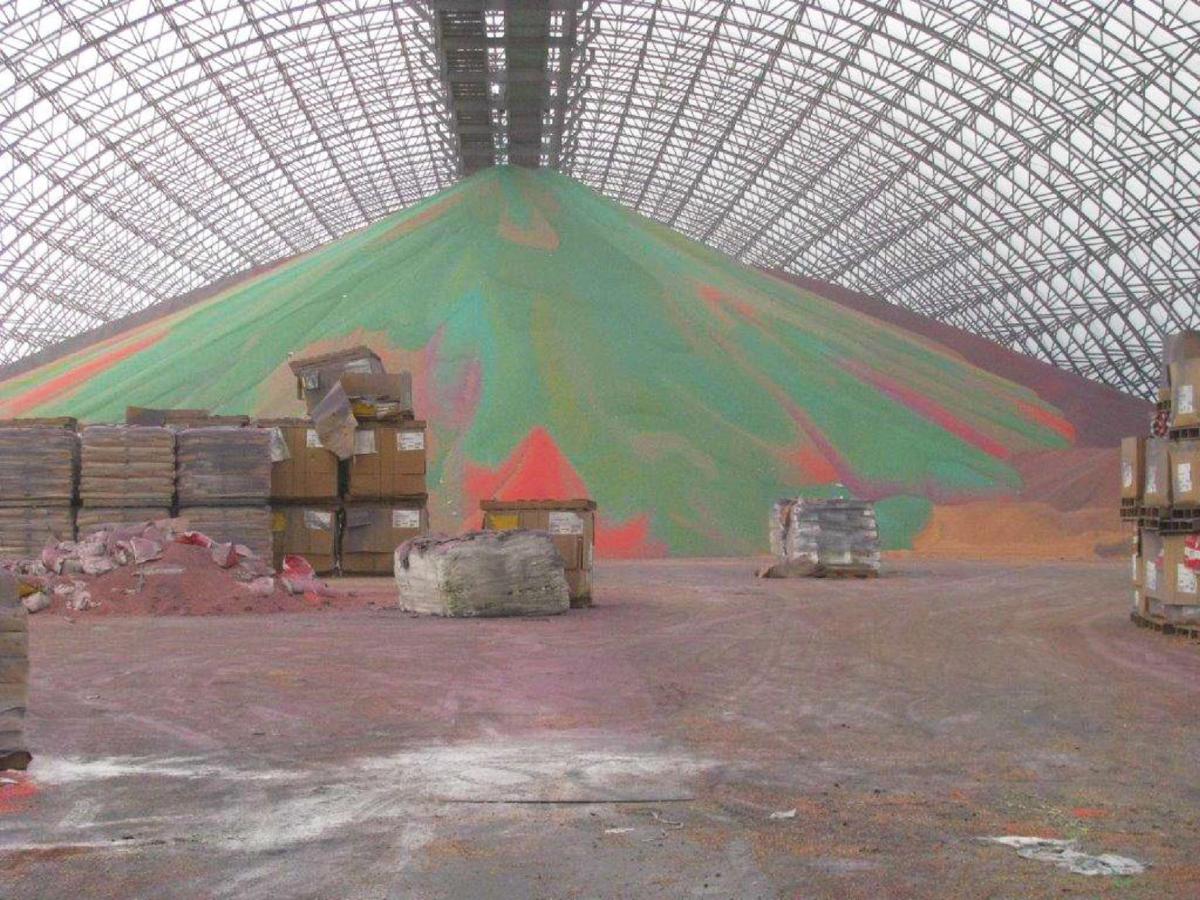

Seed treated with pesticide, which is colored to distinguish it, is piled inside a three-story building at the AltEn Ethanol plant near Mead in this photo taken in April 2019 during a Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy inspection. The seeds were used in the plant's ethanol process and the byproduct of that process created soil conditioner sold to area farmers.

AltEn, an ethanol company in Mead, uses treated seed as feedstock. The seed is colored to indicate it’s been treated with pesticide or fungicide.

AltEn was ordered on Feb. 4 to shut down its ethanol production after the state found three lagoons on the site were badly damaged and holding more wastewater than permitted. It completed the shutdown on Feb. 8, according to the Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy. This aerial photo was taken in mid-January.

Emptied treated seed bags are stacked at the AltEn company in this photo taken in April 2019 during a Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy inspection. The ethanol plant near Mead used the seeds to produce ethanol and the byproduct from the process to create soil conditioner sold to area farmers.

AltEn Ethanol has been the subject of dozens of complaints since it reopened near Mead in 2015 related to an odor coming from the byproduct of its ethanol process, seen here at the beginning of the month. The byproduct has been found to carry levels of pesticides and fungicides above limits set by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Seed bags are stacked in a three-story building at the AltEn company in this photo taken in April 2019 during a Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy inspection of the ethanol plant near Mead. The company used the seeds to produce ethanol and the byproduct from the process to create soil conditioner sold to area farmers.

AltEn, an ethanol company in Mead, uses treated seed as feedstock. The seed is colored to indicate it’s been treated with insecticide or fungicide.

Seed treated with pesticide, which is colored to distinguish it, is piled up at the AltEn Ethanol plant near Mead in this photo taken in March 2019 during a Nebraska Department of Agriculture inspection. The seeds were used in the plant's ethanol process and the byproduct of that process created soil conditioner sold to area farmers.

A year after state regulators ordered AltEn Ethanol to stop selling its pesticide-contaminated soil conditioner to local farmers, the Mead ethanol plant remained the final destination for millions of pounds of treated seed in North America.

The Nebraska Department of Agriculture issued a “Stop-Use and Stop-Sale Order” on AltEn’s soil conditioner in May 2019 after tests determined it was laced with concentrations of pesticides that far exceeded rates deemed safe by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Soon after, based on those findings, the Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy said the soil conditioner could no longer be applied to farm ground and was considered a solid waste, requiring its disposal at a permitted landfill.

That didn't stop AltEn from continuing to solicit for more discarded corn, which it used in its ethanol production, later touting itself as the industry’s “(No.) 1 choice for recycling treated and regulated seeds.”

Instead of paying to incinerate unused treated seed or paying fees to dispose of it in a solid-waste facility, seed companies could haul or ship the seed to the village located a half-hour north of Lincoln, where AltEn would accept it at little to no cost.

AltEn soon cornered the market, entering into long-term contracts with seed industry giants such as Bayer, Syngenta and Dow, as well as more than 100 smaller companies, according to an email solicitation distributed to seed companies.

At its peak, the Kansas-owned company was receiving “nearly 98% of all the discard created by the seed industry in North America,” it touted to potential customers in the Aug. 3, 2020, email, processing 600,000 to 900,000 pounds of treated seed into ethanol daily.

While it advertised itself to seed companies as a “green recycling program,” the long, tall rows of yellow-green byproduct that began to pile up on AltEn’s property after the state prohibited it from selling it as a soil conditioner to farmers led residents in the town a mile away to refer to it as something else.

Bill Thorson, chair of Mead's Board of Trustees

“They’ve said they are a recycling plant,” said Bill Thorson, the chair of Mead’s Board of Trustees. “My personal opinion: There’s a difference between a recycling plant and a dump for seed corn companies.”

'Nobody knew anything'

As a 24-year member of Mead’s planning commission, Jody Weible signed off on the 2006 conditional use permit for E3 Biofuels — AltEn’s predecessor — to power an ethanol plant with methane collected from a neighboring cattle feed yard and in turn produce fuel and nutritious feed for cattle.

She was also on the commission when it approved AltEn’s conditional use permit in 2014 as new ownership sought to restart operations after acquiring the plant in a bankruptcy sale.

Jody Weible, a former member of Mead’s Village Planning Board, said when AltEn was given a conditional use permit to run its plant, the board wasn't told the plant would use seed corn, rather than the more common field corn, to produce ethanol.

At no time, Weible said, was the planning commission told the ethanol plant they were permitting would differ from the two dozen other ethanol plants in Nebraska, which buy harvested corn to turn into fuel.

“We gave them a conditional use permit to run an ethanol plant,” Weible said. “We didn’t specify they had to use field corn. Nobody knew anything of seed corn.”

In its earliest permit applications, dating back to December 2013, AltEn “did not propose any physical or operational changes to their fermentation process” compared to that used by E3 Biofuels, according to Department of Environment and Energy documents.

In an application submitted in July 2015 to operate a compost waste facility, AltEn indicated that “(i)f discarded seed (with chemical treatment) is utilized by AltEn in the production of ethanol, the (wet distiller’s grain) produced will be unsuitable for use as feed,” and ultimately composted.

It’s unclear exactly when AltEn started using treated seed to produce ethanol. AltEn officials did not respond to questions from the Journal Star.

Complaints by the residents of Mead about the smell coming from the plant began shortly after AltEn went into operation in 2015, however.

Weible, who lives roughly three-quarters of a mile north of AltEn, was among the many area residents who developed persistent health issues once the plant started producing ethanol.

As the complaints mounted, the Nebraska Department of Agriculture learned in June 2018 AltEn was selling an unregistered soil conditioner.

A labeling specialist with the department informed AltEn that its label did not meet the requirements set forth in state law and consulted with the company about how to properly apply for the needed label.

AltEn submitted an application in October, which was later approved by the department, according to Tim Creger, a pesticide and fertilizer manager who would later conduct the official investigation into potential pesticide contamination at the plant.

“At no time did AltEn indicate on the application or any other way to NDA that the company was using treated seed as the carbohydrate source for wetcake used as the distiller’s grain soil conditioner,” Creger wrote in his report.

In the meantime, farmers in the area had unknowingly begun to apply the contaminated distiller’s grain byproduct, as well as liquid effluent from the plant.

Records kept by AltEn and Settje Agri-Services and Engineering, which provided agronomist services to area farmers, show approximately 33,400 tons of the material was delivered to fields in the area.

During an official site inspection at AltEn in March 2019, after several raccoons were found dead near a pile of soil conditioner several miles from the plant, AltEn provided Creger with a lab report of a distiller’s grain sample tested by SGS North America that showed no pesticides had been detected.

But the pesticide expert quickly noticed something unusual about the report.

The limit for detecting active pesticide ingredients in the SGS report was 1,000 times higher than the level used by South Dakota Ag Lab, the lab used by the Nebraska Department of Agriculture.

In addition to using a much-less-sensitive measurement — parts per-million instead of parts per-billion — the SGS lab report also failed to note where the sample was collected, as well as how much was provided and what protocol was followed.

AltEn general manager Scott Tingelhoff told Creger the company had ordered a sample tested because “they wanted to prove there were no pesticide residues in the wetcake.”

An official test done later by the state showed the soil conditioner contained pesticide residues at levels 85 times higher than the maximum allowed for by the seed treatment label.

Despite noting several times in the report that AltEn had not been forthcoming about its product, the Ag Department said there was no evidence that the company had tried to deliberately mislead state regulators.

“AltEn originally provided the department inaccurate information regarding pesticide residues in their soil conditioner,” a spokeswoman said, “but we have no evidence indicating that they did that intentionally.”

The treated article exemption

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act, better known as FIFRA, governs the registration, sale and application of pesticides applied to crop fields, whether by handheld sprayer, tractor or airplane.

But coat a seed with pesticides, like neonicotinoids commonly used as a seed treatment, and plant it in the ground, and the EPA no longer considers the chemical a pesticide under FIFRA.

Around since the 1980s, the “treated article exemption” says products treated with pesticides or fungicides — lumber, paints and seed, to name a few — are not considered pesticides or fungicides themselves once they leave the factory where they are treated.

The American Seed Trade Association says the exemption prevents seed companies and farmers from having to navigate duplicative regulations at the state and federal levels.

“Without the treated article exemption for seed, there would be a tremendous duplication in unnecessary paperwork and increased bureaucratic burdens — and ultimately, costs — for taxpayers and farmers,” said Bethany Shively, the association's vice president for strategic communications.

The association, which represents 750 member companies, added that the exemption does not stop chemical companies from adhering to FIFRA regulations when they apply pesticides to the seed.

A national nonprofit consisting of farmers, beekeepers and environmentalists say the problem isn't that regulations aren't followed when pesticides are applied to seed, although they argue the “treated article exemption” has been long misapplied.

“They’ve used this treated article exemption for treated seeds to say the pesticide is there to protect the seed itself,” said Amy van Saun, a senior attorney for the Center for Food Safety, which unsuccessfully sued the EPA in 2016 to close what it says is a regulatory loophole.

The pesticide coating — indicated by a brightly colored dye — is easily dusted off during machine planting or sloughed off in the soil and carried away by water, or absorbed into the growing plant, van Saun added.

At that point, she said, the pesticides are protecting something different than what they were intended to protect.

“Once those seeds are out there being planted, they don’t have to be treated like a pesticide,” van Saun said, which the Center for Food Safety said leads to an array of contamination issues.

She said the treated article exemption likely also creates a regulatory gap for seed disposal.

The EPA requires proper use and disposal of treated seed, warning manufacturers not to use the products for feed, food or oil purposes. But the labels do not rule out sending treated seed to ethanol plants if certain criteria are met.

“Excess treated seed may be used for ethanol production only if byproducts are not used for livestock feed and no measurable residues of pesticide remain in ethanol byproducts that are used for agronomic practice,” the labels from multiple companies say.

As regulators began to respond to a flurry of complaints lodged against AltEn in spring 2018 — but before they determined the byproduct contained “measurable residues of pesticide” — Creger said he had repeatedly recommended seed companies avoid sending their discarded seed to ethanol plants.

“We have tried for years to get seed corn companies to understand the ethanol process is not a best management practice,” Creger wrote in an email to representatives from NDEE, “but they tend to ignore those advisories as idle threats when they know they will either not get caught or not exceed upper-end thresholds in the byproduct.”

It would take several more years before those companies, including some of the biggest names in agriculture, would heed that recommendation.

Bayer, whose Poncho 600 product -- now owned by BASF -- contains clothianidin, a neonicotinoid found in extremely high concentrations in wastewater lagoons at AltEn as well as in waterways off the property, said it “recently paused all shipments” to the plant.

“We did so out of an abundance of caution, as questions related to the facility are resolved,” the company said in a statement.

A spokesman for Syngenta AG, which uses the neonicotinoid thiamethoxam in its Cruiser product, said it stopped sending seed to AltEn on Jan. 12 — two days after a story in the Guardian newspaper highlighted the contamination caused by the plant.

“We are reviewing the entire matter,” the company said.

‘An impossible situation’

The method used by AltEn to produce ethanol may soon become illegal in Nebraska.

State Sen. Bruce Bostelman of Brainard, whose legislative district includes Mead and the ethanol plant, sponsored a bill (LB507) this year that would prohibit the use of treated seed corn in fuel production, if the byproduct is deemed unsafe for livestock consumption or land application.

If the bill advances from the Legislature’s Natural Resources Committee and gains approval from state lawmakers, it could become the first law of its kind in the country.

Meanwhile, the Department of Environment and Energy earlier this month ordered AltEn to cease operations until it could come up with a plan to dispose of millions of gallons of contaminated wastewater on the site and repair lagoons that are in violation of state regulations.

AltEn completed its shutdown Feb. 8, according to the department.

The action by regulators and legislators is leaving many in the area wondering what will happen to the waste that has continued to build up at the plant. On Friday, a frozen pipe burst, releasing wastewater to run off from the property.

Paula Dyas' dogs (from left), Scout, Buddy and Athena, became violently ill after eating soil conditioner spread in the field behind her home. The conditioner is created with a byproduct produced by AltEn Ethanol's unusual manufacturing process, which uses seeds treated with pesticides instead of harvested grains.

Paula Dyas, who lives north of Mead and paid to have a sample of the soil conditioner tested after her dogs became violently ill, said AltEn has put itself in “an impossible situation.”

“If AltEn goes bankrupt, and that facility closes down, who’s left holding the bag?” Dyas said. “Who’s going to make sure this waste is appropriately handled? We don’t know the answer to that.”

Thorson, the village chair, said while the offensive odor coming from the plant was the first concern of many, attention has shifted to what could be a bigger problem of potential groundwater contamination.

While the village of Mead is north of the plant, the water runs south, collecting into Johnson Creek before it eventually enters the Platte River near Ashland, where the city of Lincoln has its wellfields.

The Lower Platte North Natural Resources District said it has heard — and shares — the concerns of many who have called, but general manager Eric Gottschalk said not much can be done.

Because the potential pollution originates from an identifiable location, jurisdiction to investigate whether contaminants have reached the groundwater rests with the Nebraska Department of Energy and Environment, which has ordered quarterly tests at the site.

“We just don’t have the authority to do anything in this particular situation,” Gottschalk said.

Lincoln Water System officials have also kept a close eye on the situation near Mead ever since the state notified them Jan. 12 of the potential for groundwater contamination, said Donna Garden, the city's assistant director for utilities.

For now, the city is confident the water is safe, Garden added.

“LTU estimates it would be decades before any potential pollutant from the facility site could impact Lincoln’s wellfields, which gives Lincoln Water System time to monitor the situation and work with NDEE on their findings,” she explained.

Thorson said Mead officials fear AltEn could become another federal Superfund site, like the Nebraska Ordnance Plant a half-mile south of town, and assigned blame to AltEn for not being more forthcoming about its operations.

“They’ve tried to do things behind people’s back the whole time they’ve been there,” he said. “You can’t ruin a community and an aquifer.”

TOP JOURNAL STAR PHOTOS FOR FEBRUARY

Top Journal Star photos for February

American Bison forage for food in the bitter cold after on Sunday, February 07, 2021, at the Pioneers Park Nature Center. Bone chilling winds whipped snow through the Lincoln area, causing temperatures to drop to single digit temperatures. Weekly outlooks expect the trend to continue for at least into the next week. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star.

Top Journal Star photos for February

A dog walker walks past tree branches covered in hoar frost near Holmes Lake Park on Tuesday, Feb. 2, 2021. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for February

Fremont bowling head coach Keith Cunnings celebrates after the team won the team title during state bowling championships, Tuesday, Feb. 9, 2021 at Sun Valley Lanes. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for February

Alec Manzano (right) loads an order of groceries into a car at the Hyvee online order pickup site on Sunday, February 07, 2021, at the Hyvee on 51st and O street. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star.

Top Journal Star photos for February

Venturing out in the below-zero wind chill on snowshoes he received in Christmas 2019, Walt Stroup of Lincoln blazes a trail on the pristine powdery remnants of the 25.3 inches of snow the city received during a 14-day period from Jan. 25 to Feb. 7 on Tuesday, Feb. 9, 2021, at Holmes Lake Park. FRANCIS GARDLER, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for February

Fremont's Cole Macaluso bowls in the boys state bowling, Monday, Feb. 8, 2021, at Sun Valley Lanes. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for February

Snow and single-digit temperatures don't stop people from walking around Holmes Lake on Monday, Feb. 8, 2021. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for February

Nebraska's Kaitlyn Higgins springs from the vault during a duel against Rutgers on Sunday, Feb. 7, 2021, at the Devaney Sports Center. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star.

Top Journal Star photos for February

Shadows of the Lincoln East show choir are silhouetted on the wall as they rehearse on Monday, February 01, 2021 at Lincoln East High School. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star.

Top Journal Star photos for February

Nebraska head coach John Cook (bottom center) talks to the team before they take on Maryland on Saturday, Feb. 6, 2021, at the Devaney Sports Center. FRANCIS GARDLER, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for February

A biker braves heavy snowfall on Saturday, Feb. 6, 2021, along the Rock Island trail. Adverse weather was of no concern to the cold blooded bikers who took part in the Frosty Bike Ride on Saturday. Despite temperatures in the low teens and a snow forecast of 4 inches, bike enthusiasts braved the weather for the annual ride. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star.

Top Journal Star photos for February

Lincoln Southwest's Tommy Palmer launches himself into the backstroke at the start of the Boys 200-Yard Medley Relay against Lincoln Southeast on Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021, during a swimming dual at Lincoln Southwest High School. FRANCIS GARDLER, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for February

Proponents of LB643 wait in the rotunda to testify in favor of the new bill on Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021, at the Nebraska State Capitol. If passed LB643 would allow them to be exempted from any vaccine program, though at this time one does not exist. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star.

Top Journal Star photos for February

By-product of ethanol is seen at AltEn, Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021, in Mead, Neb. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for February

Hoar frost coats tree branches on Tuesday, Feb. 2, 2021. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for February

Crew members work around an OC-135B after it landed as the first U.S. Air Force plane from Offutt's temporary relocation to the Lincoln Airport on Monday, Feb. 1, 2021. The Air Force's 55th Wing is relocating to Lincoln while Offutt's runway is reconstructed. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Journal Star reporter Riley Johnson contributed reporting.

Reach the writer at 402-473-7120 or cdunker@journalstar.com.

On Twitter @ChrisDunkerLJS

February 14, 2021 at 09:00PM

https://ift.tt/3jMz19y

'A dump for seed corn companies' — Mead residents worry what comes next for troubled ethanol plant - Lincoln Journal Star

https://ift.tt/3gguREe

Corn

No comments:

Post a Comment