Marianne Eaves, Distiller and Lindsey Hoopes, Proprieter, Hoopes Vineyard

Photo, courtesy Jillian Mitchell/Hoopes VineyardIn recent years forest fires have become a perennial problem for West Coast winemakers. When wood burns a range of phenolic compounds are released into the air. The closer a vineyard is to a fire, the greater the concentration of phenolic compounds to which the grapes are exposed.

When these phenols come into contact with maturing grapes they bind with the sugars in the grapes to create phenol-glycosides. The phenomenon is called smoke effect or smoke taint. These compounds are tasteless and odorless. Over time, starting with fermentation and proceeding through maturation and post bottling, however, they break down releasing phenols into the wine and creating smoky, medicinal, ashy, charred wood and other phenolic flavors that typically make the wine undrinkable.

Human sensitivity to phenols varies widely, but they are typically discernable in concentrations as low as two to three parts per billion. To put this concentration in perspective, that’s the equivalent of 12 seconds out of a century.

One solution, which some West Coast winemakers are increasingly turning to, is distilling their wine into a spirit, typically a grape brandy. Unlike wine, phenols can enhance the aroma and flavor profile of a spirit. A phenomenon long appreciated by lovers of peated Scotch whiskies, especially the heavily peated expressions produced on the island of Islay off Scotland’s west coast.

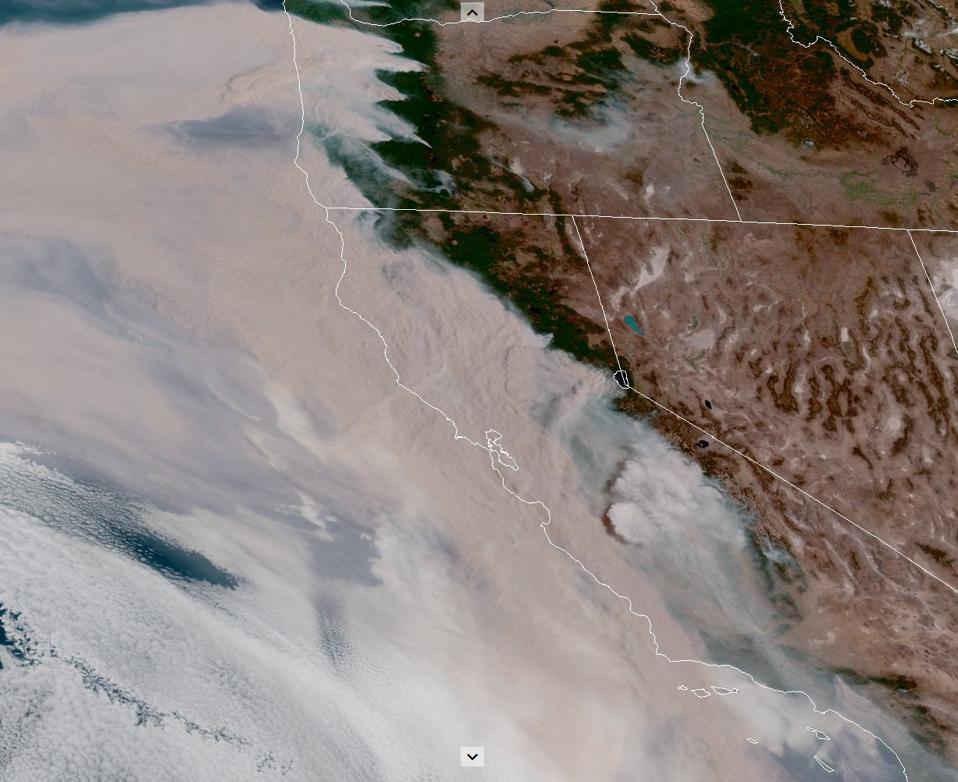

2020 forest fires blanket the west coast of the United States

PHOTO, COURTESY GOES-17/US NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICEMORE FOR YOU

Distilling wine that would otherwise be unsaleable has another advantage. Higher alcohol levels mask the phenolic flavors in the resulting spirit. Typically, in an 80 proof/40% alcohol by volume (ABV) beverage, phenolic flavors don’t become discernible until they reach concentrations of two to three parts per million—that’s a thousand times higher than in wine.

Being both a winemaker and a distiller, however, isn’t easy. Recently, I sat down with Lindsey Hoopes, a second-generation Napa winemaker and a first-generation distiller, to talk about the challenges winemakers face when they turn to distillation to salvage smoke tainted grapes and wines.

JM: What persuaded you to add distilling to your wine production activity? Was this a specific response to coping with smoke affected grapes/wine or was it independent of that?

LH: I have always been a Scotch fan, and as of late a Japanese whisky enthusiast, but never had any intention of creating a spirit-based product myself—until the 2017 fires happened. Our insurance claims were denied so we turned to distillation to find a solution to grapes that were unsuitable for quality wine production.

In my estimation, spirits and wine are within the larger beverage category, but are very different products. They require substantially different business models and a lot of additional resources, skills, etc. They are not the most obvious, or successful, brand extension for a producer of either one. Distillers rarely make wine and winemakers don’t often dive into the world of distilling.

JM: Compared to spirits, wine, usually, has a much shorter maturation cycle. How do the economics of distilling spirits compare to winemaking?

LH: Wine does not necessarily have a shorter maturation cycle than spirits. In my experience, however, making table wine first and then converting the wine into a spirit is a longer process than simply releasing the product as wine. Our time to market has been extended by at least three years, at a minimum, over the wines that we produced.

You could of course make wine, distill, mature and release brandy in two years. That would be about the same as wine if you had the end-goal of just making a generic brandy from the beginning of the harvest process.

I agree that most high-end, rare, or coveted spirits are appreciated because of their extended maturation process—so to compete at a higher price-point or perceived quality level, we had to consider maturation and develop a process for maturation that was going to give us a product that we were proud of, was of the highest quality, and of course, delivered the intended results—something that would complete, for example, with the highest quality wine-based products from Cognac.

The process we are undertaking is absolutely not economical or for the faint of heart. We make wine in one of the most expensive winegrowing regions in the world, Napa, and pay Napa prices to convert the grapes into wine. Even though the wine would eventually become a spirit, we took no shortcuts during the production of the base wine. We treated it as though the wine would end up in bottle as an ultra-premium Napa wine.

In 2017, we aged the wine and proceeded with the highest quality process—inclusive of two-years of aging—before we determined that we could not sell the wine in good confidence as a high-quality wine product.

You lose about 85% of the volume of the wine when you distill it, so our actual saleable volume changes dramatically.

Then you must mature the distillate according to legal restrictions and quality parameters after distillation. It’s expensive, of course, new barrels, new team (distillers, not winemakers), specialized storage for distillates, etc. It’s really two different facilities and operations.

It’s much more expensive to make Napa wine, than spirits generally, because of the cost and quality of the substrate—Napa grapes are expensive for wine, and even more expensive if used for spirits. Of course, how long you age the spirit will also impact the costing.

You don’t have to temp control spirits barrels, so it’s easier to age than wine. The most expensive product you could imagine is the combination of the two—Napa grapes into a quality wine and then spirits.

JM: Most brandies are based on white grapes. Your brandy production is based on red grapes. How does the aroma and flavor profile of red grape-based brandies differ from conventional brandies?

The Hoopes Vineyard, Napa Valley, California

Photo, courtesy Hoopes VineyardLH: All of our brandy is from red grapes. I was personally surprised that few people have made brandy from red grapes. It may be because the origin of the spirit is based around grapes that weren’t best utilized in wine as the end-product. The red grapes that we used—primarily cabernet—provided a unique aroma and flavor profile from any brandy I had previously tasted.

Our distiller, Marianne Eaves, describes the process this way:

There is a very similar correlation in the world of Bourbon and beer—basically Bourbon makers brew beer, but it doesn’t taste very good because the flavors are developed in a specific way, using specific grains, that lean toward the expected profile in the aged distillate.

The very same thing happens in brandy making—distillers ferment a neutral white grape to attain certain flavors that are already understood through traditional industry practices to make great brandy/Cognac.

Winemakers and brewers, on the other hand, use very flavorful grapes/grains and pay very close attention to the flavor in the fermentation because they have limited options to further change the flavor. The more flavorful, wine intended, grapes produce a distinctly different distillate. Some traditionalists may turn up their nose at it, but others will appreciate the complexity and boldness of the resulting spirit.

JM: Phenol concentrations in wine are discernable, for most people, in parts per billion whereas in spirts that threshold is a thousand times higher and is measured in parts per million. Are there phenol levels in wine where it is no longer feasible to distill into brandy?

LH: I don’t know. Probably, but we haven’t found the level yet. We intend to play around with the grapes in a smoke chamber to see if there is a tipping point and actually have built all our spirits as though they were single vineyard lots so far so we can control the influence of any one site.

So far, our phenol levels were very unsuitable for wine, but very pleasant in spirits—so it seems that you could use grapes with significant smoke exposure and high guaiacol levels, etc. and still have a pleasant spirits product. We have only had two fires, although we had multiple levels of smoke taint, and none have been unpleasant in the distillate to date.

JM: Would you manage grapes being cultivated for brandy production differently from those intended for wine production i.e., would you crop higher yields, pick earlier (to increase acidity) or later (to maximize sugar levels)?

LH: I imagine you might want to manage your vineyard differently if you wanted to transition to brandy making as your sole output. I do not plan to harvest differently, however, because we make wine, first, and now make brandy as well. So, we approach the farming from the perspective of winemaking. I think spirits could endure shortcuts in the farming, whereas wine cannot—at least not with our quality expectations.

JM: Grapes/wines that are intended for distillation are not treated with sulfites since these compounds can create off flavors in distillation. How do you handle wines that were treated with sulfites or do you have to make the decision to earmark grapes for distillation before they are even picked? How can you determine if smoke taint is going to be a problem before the grapes are even picked much less made into wine?

LH: Traditionally, yes, brandy makers do not treat their base wines with sulfur. However, there are ways to de-sulfur a finished wine. The addition of hydrogen peroxide binds free sulfur and it is then removed during the distillation process. It’s just a matter of taking the proper heads and tails cuts.

In 2020 all grapes were earmarked for brandy rather than wine production because the wildfires broke out early. We did not need to de-sulfur the wines like we did with 2017. That said, our process would depend on Mother Nature and how/when/to what extent wines were affected with smoke and when the phenols presented in the process.

JM: Thank you.

The Link LonkDecember 20, 2020 at 07:00PM

https://ift.tt/2LV4Znp

Why Smoke Damaged Grapes Are Causing Some Wine Makers To Become Distillers - Forbes

https://ift.tt/3eO3jWb

Grape

No comments:

Post a Comment